There are significant differences that may arise between intangibles valuations undertaken for financial reporting purposes (specifically in a purchase price allocation, or “PPA,” context) versus valuations undertaken for transfer pricing.

Comparison of PPA and TP Valuations1

There are significant differences that may arise between intangibles valuations undertaken for financial reporting purposes (specifically in a purchase price allocation, or “PPA,” context) versus valuations undertaken for transfer pricing. Stakeholders need to understand why PPA valuations should not necessarily be used for a transfer pricing analysis (for example, for integration of acquired intangibles into existing tax structures).

The OECD and various tax authorities have indicated that while valuations of intangible assets prepared for financial reporting may provide a useful starting point for a transfer pricing analysis, such valuations may not be sufficient if an intercompany issue exists. While there is some similarity and overlap in the data gathering and identification of functions, assets, and overall scope of the analyses, there are also key differences that need to be taken into consideration:

- Standards of value-For US financial reporting purposes under ASC 805, the standard is “Fair Value”, as defined in ASC 820. Fair Value measurement is based on assumptions of what factors “market participants” would evaluate in pricing the asset. Transfer pricing regulations depend upon “arm’s-length” prices. While the two standards are similar in nature, they are not identical. Factors that might affect pricing between parties at arm’s-length extend beyond those that market participants would consider. (One example is buyer-specific synergies – relevant for transfer pricing, but not for financial reporting.)

- Intangibles definitions and groupings-The manner in which intangibles are defined and bundled under Fair Value and tax transfer pricing analyses often differs, and the resulting risk and value implications can be significant. For financial reporting, intangible assets are non-monetary assets that cannot be seen, touched, or physically measured, which are created through time and/or effort, and that are identifiable as separate assets. These intangibles provide control over a resource, and are expected to provide future economic benefits. For transfer pricing, intangible assets are defined as ‘non-routine contributions’ that can be bundled together and are often broader and more inclusive than assets defined for financial reporting.

- Remaining economic lives-For financial reporting purposes, an intangible asset can be characterized as either finite-lived or indefinite-lived. The valuation of finite-lived intangibles often excludes their contribution to future intangible development. In contrast, for transfer pricing purposes, the projected contribution of existing intangibles to future intangible development efforts needs to be taken into account.

- Valuation methods-The generally acceptable valuation methods for financial reporting and transfer pricing purposes are also similar, and all fall under one of the three general valuation approaches: (i) the income approach, (ii) the market approach, and (iii) the cost approach. However, there are differences between financial reporting and transfer pricing in terms of the application of those approaches. One example is the income approach:

- For financial reporting, two income-based methods that are generally used are: (i) the multi-period excess earnings method (“MPEEM”), or, (ii) the relief-from-royalty method (“RFRM”). Both methods require the selection of an appropriate discount rate commensurate with the risks associated with that specific intangible. For transfer pricing, the most common application of an income approach calculates the Net Present Value of profits attributable to a portfolio of intangibles, net of profits ascribed to routine functions. We note that the income method for transfer pricing takes a functional orientation around a group of intangibles, whereas the MPEEM takes an asset orientation and typically focuses on an individual intangible.

- Consideration of taxes- Assumptions regarding income taxes are often different for Fair Value and transfer pricing intangibles valuations because they are performed for different purposes. In a typical financial reporting context, intangibles valuations are performed on an after-tax basis (i.e., apply after-tax discount rates to after-tax income streams). However, for transfer pricing purposes, intangibles value may be determined through the application of post-tax discount rates to pre-tax income, or other variations in some circumstances.

Despite the potential differences in financial reporting versus transfer pricing valuations, companies should perform valuations of acquired IP for PPA and (potential) transfer pricing purposes jointly. This practice can save time and money (e.g., through joint interviews and information gathering) and, though the valuation results will likely differ, helps ensure consistency of the basic data and assumptions used. Consequently, a joint analysis can reduce both domestic and foreign tax exposures and audit risks.

Transfer Pricing in the Energy Industry2

Transfer pricing is one of the most important tax issues facing multinational energy firms. Given the complexity, integrated nature, and capital intensity of the energy industry, an extensive amount of intercompany activity takes place, particularly within large, vertically integrated multinationals. Consequently, transfer pricing can have a substantial tax impact, including potentially sizable adjustments to reported income. We highlight here the more common intercompany transactions in this industry, including issues that may arise in complying with transfer pricing regulations (from a US perspective).

In terms of revenues, the sale of tangible products is the largest type of intercompany transaction found in the energy industry. We must consider the following issues:

- While previously considered sacrosanct, the IRS is taking a greater interest in understanding commodity transactions given the typically high volumes and the possibility of material adjustments. Furthermore, the IRS is beginning to challenge the taxpayer’s selection and application of transactional methods.3

- Given the need for asset mobility in the industry, the intercompany sale and leasing of specialized equipment and/or tools from the owner to a service provider is also prevalent. Determining an arm’s-length transfer price can be difficult as it is typically hard to find good comparables for such transactions; as such, many taxpayers are employing profit-based approaches to support their pricing.

The second largest type of intercompany transaction, which is embedded in all aspects of the energy business, is the provision of services. Relevant issues include:

- Services are typically charged at cost or at cost plus a mark-up. As is the case in most industries, the IRS’s focus is not only on the mark-up applied, but on the appropriateness of the cost base. The fact that independent parties in joint ventures typically exchange services at cost adds another layer of complexity in the energy industry.

- For high-value, high-skilled services (e.g., engineering/technical services) the IRS has questioned whether these are pure services or rather services bundled with intangible property (“IP”).

- Secondment arrangements are also under scrutiny by the IRS given the potential for transferring valuable IP during the secondment period.

Other notable types of transactions in the energy industry include:

- The use of specialized equipment/tools gives rise to substantial licensing of related IP (primarily know-how) from an IP owner to a related manufacturing entity. One of the major complicating factors is that IP can be developed by joint ventures/consortia, which can create ambiguity when defining ownership. One option for overcoming this obstacle is the use of cost sharing arrangements.4

- Intercompany financing transactions, which have faced increased scrutiny from the IRS given the capital investment required in this industry.

With transfer pricing audits increasing in significance, intrusiveness, and scope, and given the unique aspects of the energy industry in general, multinationals have a greater than ever need to support their transfer pricing policies in the context of value drivers in their industry, through comprehensive documentation and planning.

Court Decision Could Lead to Tax Risks for PE Firms

A noteworthy legal decision over the summer could have far-reaching ramifications for private equity (“PE”) firms. The First Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals (“the Court”) held that a Sun Capital Partners fund can be held liable for unfunded pension liabilities incurred by one of its portfolio companies (which went bankrupt). The Court found that the fund was not merely a passive investor in the company, but rather was engaged in a “trade or business” by virtue of its (the fund’s) economic interest in the management of that company. In this case, the Court focused on the fact that management fees paid by the portfolio company to a subsidiary of the general partner (“GP”) resulted in offsets to the management fee payable by the fund to the GP, hence the direct economic interest. Even without such an offset, however, any PE fund directly benefits from the activities of the GP and its subsidiaries, and so might in the future be deemed as having a trade or business via its investments (i.e., piercing the “passive investor veil”).

Although this decision did not address tax issues, some relevant questions are raised by it:

- The fund was found to be engaged in a trade or business for purposes of the ERISA act, but might the same argument be made for tax purposes?

- Specifically, might PE funds, and their investors, be held responsible for transfer pricing adjustments and penalties imposed by tax authorities on portfolio companies?

- Further, can a tax authority argue that a PE fund has a “permanent establishment” (i.e., a taxable presence) in a given jurisdiction due to its investment/management of a company in that jurisdiction? If so, would this lead to a tax liability for the fund investors in that jurisdiction?

The First Circuit decision is limited to pension provisions under ERISA, so its extension to tax and transfer pricing is speculative at this point. However, this could be a step toward holding PE funds and their investors to greater accountability for the activities of portfolio companies, including those related to transfer pricing. In addition, there could be tax exposure for the fund itself, based on its structure and investments.

India Issues Draft on New Safe Harbor Rules5

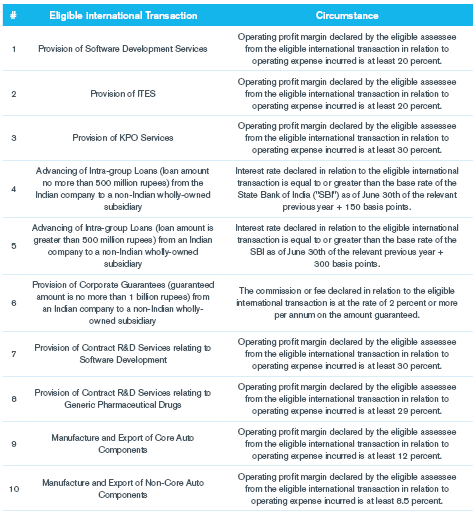

On August 14, 2013, the Indian Central Board of Direct Taxes (“CBDT”) issued a draft of proposed safe harbor rules (the “CBDT Draft”) in an attempt to reduce the number of audits and prolonged disputes between taxpayers and tax authorities. For the purposes of the Draft, a safe harbor is defined as a stated margin or rate at which the CBDT shall accept the transfer price declared by the assessee. The CBDT Draft is limited in scope, as it applies only to the following sectors/activities (“eligible transactions”):

- Software Development Services;

- Information Technology Enabled Services ("ITES");

- Knowledge Processes Outsourcing ("KPO") Services;

- Intra-group Loans;

- Corporate Guarantees;

- Contract Research and Development ("R&D) in the IT and Generic Pharmaceutical Industries; and,

- Auto Equipment Manufacturers (both core components and non-core components).

We highlight the key circumstances under which the transfer price declared by the assessee in respect of such eligible transactions will be accepted by the Indian tax authorities in the table below.

The provisions summarized in the table above would be effective for assessment years 2013 – 2014 and 2014 – 2015. Furthermore, in order to be eligible for the safe harbors proposed in the CBDT Draft (i.e., an “eligible assessee”), a taxpayer must meet the following criteria:

- For entities engaged in the provision of software development, ITES, KPO, or R&D services, the associated foreign entity must, on behalf of the Indian assessee, perform most of the economically significant functions, provide necessary capital and funding, deliver direct supervision, and assume all ownership rights to any intellectual property generated in India.

- Indian entities must face “insignificant risk,” though the Draft lacks a clarification as to what is considered “insignificant.”

- For entities engaged in the manufacture and export of core and non-core auto components, 90 percent or more of total turnover during the relevant previous year must be in the nature of Original Equipment Manufacturer (“OEM”) sales.

- For Loans and Guarantees, only transactions involving “wholly owned subsidiaries” qualify.

- The foreign associated enterprise in the transaction must not be located in a no-tax or low-tax country or territory.

All taxpayers, regardless of whether they elect to use the safe harbor, must continue to comply with the existing documentation requirements. However, if a taxpayer elects to use the safe harbor provisions proposed in the CBDT Draft, the taxpayer must also complete and submit Form 3CEG (a copy of which is available as part of the CBDT Draft). It is important to note that by accepting the transfer price given in the CBDT Draft, assessees will forfeit all additional comparability adjustments or allowances, as well as lose all claims to invoke mutual agreement procedures.

Comments on the CBDT Draft were accepted until August 26 of this year, and the CBDT is expected to issue final rules based on received comments. No official timeline has been released for the completion.

1.For more information, please see “Bridging the Divide between Financial Reporting and Transfer Pricing,” Nathan Levin and Jill Weise, Financial Executive, July / August 2013 (www.financialexecutives.org).

2.For more detailed information see our contribution in BNA’s Transfer Pricing Forum, 07/13, ISSN 2043-0760.

3.The IRS has developed a handbook specifically for examining taxpayers within the oil and gas industry. See, IRS Oil and Gas Handbook – Chapter 41 of Internal Revenue Manual (http://www.irs.gov/irm/part4/irm_04-041-001.html).

4.See US Regulations Section 1.482-7.

5.The Draft can be found on the CBDT website (http://www.incometaxindia.gov.in/archive/BreakingNews_DraftSafe_14082013.pdf).

Stay Ahead with Kroll

Valuation Services

When companies require an objective and independent assessment of value, they look to Kroll.

Tax Services

Built upon the foundation of its renowned valuation business, Kroll's Tax Service practice follows a detailed and responsive approach to capturing value for clients.

Transfer Pricing

Kroll's team of internationally recognized transfer pricing advisors provide the technical expertise and industry experience necessary to ensure understandable, implementable and supportable results.

Valuation Services

When companies require an objective and independent assessment of value, they look to Kroll.