States seek tax system for the new millennium: Court to hear case in April

Online retail wasn't much of a big deal in 1992. Come to think of it, it wasn’t a deal at all. A lot of people were still getting used to email, and Jeff Bezos had just started selling books out of his garage for a small start-up company he called Amazon.com (“Amazon”). Bezos was particularly excited by the growth of internet use and how it could coincide with a new U.S. Supreme Court ruling that exempted mail order companies from collecting sales taxes in states where they lacked a physical presence.

That would be the 1992 Quill v. North Dakota (“Quill”)1 decision, which stated that a catalog or online retailer did not have to collect a state's sales tax if the retailer had no physical presence (or nexus) in that state. While this system may have made sense when you were ordering a pocket watch from Sears, Roebuck & Co., times have changed a bit. Quill has become a seminal case for online retailers, not only because it meant they essentially didn't have to pay state and local sales taxes, but also because it allowed them to offer ultra-competitive prices compared to traditional brick-and-mortar stores. It also meant that local governments, which rely heavily on sales taxes, lost enormous amounts of revenue as more and more commerce moved online.

In fact, the Government Accountability Office, which provides nonpartisan reports to Congress, estimated that local governments would have gained between $8.5 billion and $13 billion in 2017 if they could have required remote sellers to collect tax on sales into the state2. Of course, the issue becomes even more precarious as we watch online sellers become some of the most profitable companies on the planet. Traditional sellers can’t keep up, and the states are at their wits’ end trying to capture sorely needed taxes from the online retail explosion.

Not to be ignored, President Donald Trump has even weighed in, striking a rare blow against business interests when calling out Jeff Bezos and Amazon for avoiding-until recently- its obligation to collect state sales tax3.

Despite longstanding criticism, Amazon made a concerted effort to get out in front of the sales tax issue by collecting tax in all jurisdictions in 2017. At this point, they had built warehouses all over the country, meaning they have a physical presence in many states and would be subject to sales tax. However, Amazon still avoids charging consumers sales tax when they buy products from one of its third-party vendors, which makes up a significant portion of its business. For those items, the company says it’s up to the sellers to collect taxes, but many of them don’t.

The primary impetus for the Court coming back to this issue is most certainly due to comments made by Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy in 2015 when he stated the following in Direct Marketing Association v. Brohl:

“The Internet has caused far-reaching systemic and structural changes in the economy, and, indeed, in many other societal dimensions…Today, buyers have almost instant access to most retailers via cellphones, tablets and laptops. As a result, a business may be present in a state in a meaningful way without that presence being physical in the traditional sense of the term. Given these changes to technology and consumer sophistication, it is unwise to delay any longer a reconsideration of the Court’s holding in Quill. A case questionable even when decided, Quill now harms States to a degree far greater than could have been anticipated earlier.”

He then basically threw down a gauntlet: “The legal system should find an appropriate case for this Court to reexamine Quill.”

Enter South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc. On April 17, 2018, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in a case where South Dakota is hoping the high court will see that Quill is obsolete in the e-commerce era and will consider freeing state and local governments to collect billions of dollars in sales taxes from online retailers.

And it took you this long, because…?

The physical presence rule is a constitutional debate that has been stewing for decades. While modern discussions on the issue tend to start with Quill, it really started in 1967 with the National Bellas Hess v. Department of Revenue of Ill case4 (“National Bellas Hess”), where the Supreme Court reviewed and rejected an attempt by the State of Illinois to require the National Bellas Hess Company, a mail order company based in Missouri, to collect its use tax. The state statute at issue imposed the tax-collection requirement based solely on that company’s solicitation of orders within the state through the use of catalogs or other advertising. The Supreme Court held that the state’s requirement was unconstitutional, noting that it had never before authorized the imposition of tax-collection obligations on vendors “who do no more than communicate with customers in the state by mail or common carrier as part of a general interstate business.” It “declined to obliterate” that line, and the physical presence rule was born.

By the late 1980s, North Dakota was so frustrated that it modified its law to impose tax collection obligations on retailers, like Quill Corp., who targeted in-state customers through three or more advertisements in a 12-month period. Physical presence didn’t matter. That obligation seemed to clearly conflict with National Bellas Hess, but the North Dakota Supreme Court upheld the state statute anyway, stating that National Bellas Hess was no longer controlling given the “wholesale changes” in the economy, technology and law that had occurred in the intervening years. Makes sense, right?

Not so fast. While this seemed like an opportunity for the U.S. Supreme Court to nip this growing resentment in the bud when ruling on Quill in 1992, they disagreed and upheld the physical presence rule as a Dormant Commerce Clause – a legal doctrine that prevents states from interfering with interstate commerce unless authorized by Congress. While it’s important to note that the Supreme Court at that time did not express much love for the rule, it did feel that upholding it was the best course of action given the principle of stare decisis, and the fact that Congress could always intervene using its affirmative Commerce Clause power. Congress, however, has had a rare fit on non-intervention when it comes to this issue.

This is where we need to start keeping track of our clauses to fully understand Quill, and what is currently being questioned in Wayfair. The Due Process Clause and Commerce Clause, for example, help shape the world of sales taxation today, as do the terms "minimum connection" and "substantial nexus."

- Due Process Clause: No state shall "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." With respect to state taxation, the Supreme Court has interpreted this to prohibit a state from taxing a corporation unless there is a "minimal connection" between the company and the state in which it operates.

- Commerce Clause: Authorizes Congress to "regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States." The Supreme Court has ruled that the Commerce Clause prohibits states from enacting laws that might unduly burden or inhibit the free flow of commerce between the states. In Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady, 430 U.S. 274 (1977), the Supreme Court ruled that the taxpayer must have "substantial nexus" with the taxing state in order for the state to impose its tax on the taxpayer5.

The Supreme Court was very literal in its application of the above constitutional guarantees to retailers such as Quill. When North Dakota attempted to impose upon Quill Corp. the obligation to collect the state's use tax, the North Dakota Supreme Court ruled that Quill had substantial nexus, and that it had “sufficiently availed itself of the services and benefits of the state by virtue of its business relationship with North Dakota customers.” The U.S. Supreme Court, however, reversed the lower court's ruling, indicating that while Quill had met the minimum connection standard of the Due Process Clause, it had not met the sufficient nexus standard of the Commerce Clause6.

The distinction between the economic and physical presence may be a small, but very important distinction that has cost the state billions of dollars in lost tax collections over the past 25 years. The Court upheld its earlier ruling in National Bellas Hess. The problem being, of course, most e-commerce business does not create a physical presence (or substantial nexus). Therein lies the rub, still, for states attempting to collect taxes from online sellers.

OK, we’re here. Now what?

Which brings us to the present day boiling point with South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc., where we have the state taking its own respective swing at Quill. In 2016, the South Dakota legislature enacted a statute that imposed tax collection obligations on remote vendors based solely on their economic connections with the state, with a revenue threshold of $100,000 and a transaction threshold of 200. The statute was enacted specifically to get the issue before the Supreme Court, and the litigation progressed quickly. The state admitted that its statute was facially unconstitutional, supported the defendants’ motion for summary judgment and requested that the state’s high court use its opinion to provoke the Supreme Court to grant cert and overturn Quill.

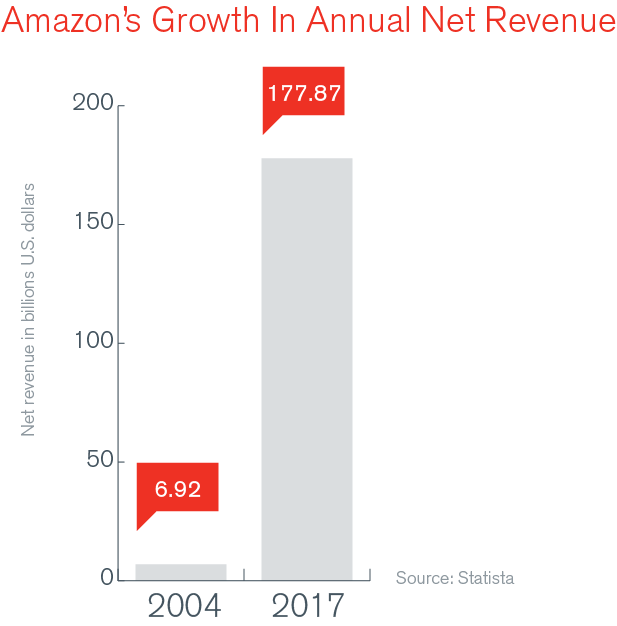

And who can blame them? We can all probably agree that nobody could have foreseen in 1992 (much less 1967) that online retail sales would produce such behemoths as Amazon, with its incredible financial and cultural impact. We’re talking percentage of GDP here. Not to mention altering basic human behavior. But today, well, the numbers speak for themselves.

So, what does a state like South Dakota, that has no income tax and relies heavily on sales tax, do to solve their inability to tax internet sales? Well, don’t try asking Congress for help, even though Quill left the door open for them to offer it. Again, it’s important to remember that, yes, the Court ruled then that a business must have a physical presence in a state for a state to require it to pay sales tax, but it also allowed Congress to override that decision if it chose to do so in the future. And again, that never happened.

Though, Congress has toyed with the issue of untaxed remote sales for years. The Senate approved the Marketplace Fairness Act (MFA) of 2013, which sought to grant states with simplified sales tax laws the right to tax certain remote sales. However, the measure was held in the House Judiciary Committee. Later iterations of the MFA and at least two versions of a similar measure, the Remote Transactions Parity Act, have never made it to the floor of the House. In 2013, when the Supreme Court, without comment, turned away appeals from Amazon and Overstock in their petition against a New York court decision that forced them to remit sales tax, Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, D-N.D., who was North Dakota’s tax commissioner when the Court issued its 1992 Quill decision, said, “It’s past time that we create a federal system to require online retailers to collect and remit sales tax, just like local shops are required to do.”

Wait, how much?

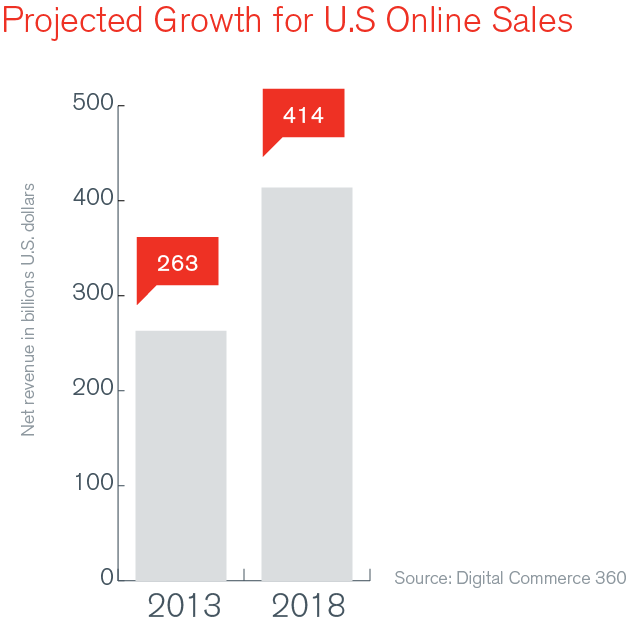

If you’re wondering why so many people from so many different camps are fighting tooth and nail over this issue, and why it has taken so long to come back to the Court, you have to consider what’s at stake. All but five states—Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire and Oregon—impose sales taxes, meaning South Dakota v. Wayfair is a national issue. Considering the projections for online sales growth over just the next year, it’s easy to see why states are becoming more aggressive to get in front of the Court again.

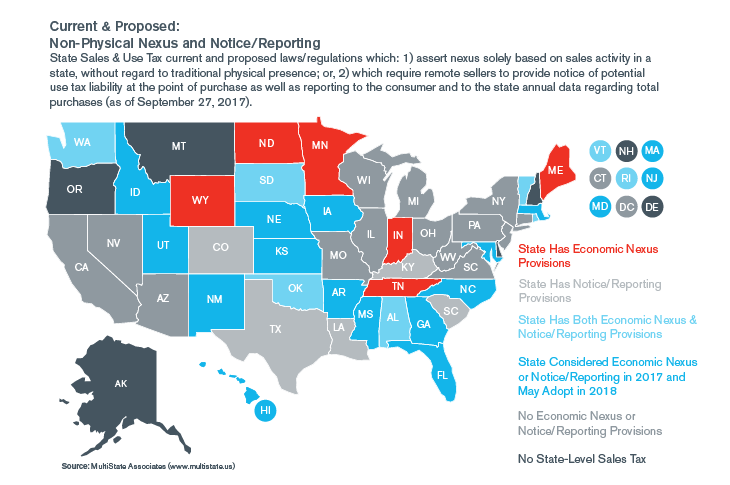

For state governments, online retailers, the U.S. Supreme Court, and all-important online shoppers, there’s obviously a lot riding on South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc. The bottom line is something has to be done, and fast. Many states, frustrated at being hamstrung by Quill, are currently ignoring that precedent, and absent the Court’s action—or legislation from Congress—this could result in a complex and indefensible patchwork of laws that could mangle interstate commerce. Since hearing of Justice Kennedy’s opinion, a number of state legislatures have already passed or are considering passing legislation requiring remote vendors to collect sales tax. Examples of broad interpretations of Quill in recent years include some states arguing that internet “cookies” can create a physical-presence nexus, and that the use of intangible property can create the “functional equivalent” of a physical presence.

“Before anything else, preparation is the key to success.” -- Alexander Graham Bell

While there seems to be an opportunity for the Supreme Court to deliver much-needed guidance on this issue, tax advisors, CFOs and taxpayers alike will need to stay well aware of how these changes affect their state and local tax structure. For example, a company with extensive national sales could be required to maintain compliance with more than 10,000 tax jurisdictions at the state level, each having a unique statutory scheme. Preparation to accommodate this sharp increase in filings will be necessary to properly process sales transactions and collect the correct amount of tax from customers.

The Court is set to hear arguments on April 17, 2018 in South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc., with a ruling possibly by the end of its nine-month term in June 2018. There are certainly many good arguments for overturning Quill. Some of the best minds of business, academia and government have said as much. Ultimately, most of those involved realize the time has come to build a rational system for handling multi-jurisdictional tax issues like this one.

How To Prepare For The Ruling

Should the physical presence requirement be re-defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, here are some areas of efficiency that businesses should carefully consider:

- Navigating the new nexus footprint

- Flexibility in monitoring taxability of goods and services

- Adaptability with revenue sourcing, invoicing and appropriate line item billing

- Keeping up with ever-changing state and local sales and use tax rates

- Complying with sales and use tax filing responsibilities

- Record retention requirements associated with online activities

For more information on how you can prepare for changes in state and local tax collection obligations on remote and online vendors, contact Robert Peters or Mary Alice Cashin in Duff & Phelps' Unclaimed Property and Sales and Use Tax practices.

Sources:

1 Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992)

2 “Supreme Court to hear South Dakota sales tax collection case.” USA Today-Argus Leader, 12 Jan. 2018, https://www.argusleader.com/story/news/politics/2018/01/12/supreme-court-hear-south-dakota-sales-tax-collection-case/1029701001/.

3 “Here’s the controversial tax practice by Amazon that’s got Trump so upset.” MSN-CNBC, 29 Mar. 2018, https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/companies/heres-the-controversial-tax-practice-by-amazon-thats-got-trump-so-upset

4 National Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Dep’t of Revenue of Illinois, 386 U.S. 753 (1967)

5 Complete Auto Transit, Inc. v. Brady, 430 U.S. 274, 284-85 (1977)

6 Miles, Monika. “Commerce Clause, Due Process and Quill Corp.” STS Publishing, LLC, http://www.salestaxsupport.com/sales-tax-information/sales-tax-101/commerce-clause-due-process-and-quill-corp/.